Cold War II

by Andrew Dowler, Managing Director of Government Relations for Blackstone in Europe

Before Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the political consensus was that Vladimir Putin was all “jaw jaw” rather than “war war”. Many argued that for him to enter a war he could never win, with or without huge suffering on his own side, would be wholly illogical. US and UK military intelligence said differently but were ignored. The West’s 20-year policy of giving Putin the benefit of the doubt held, paving the way for the greatest failure of European political due diligence since the Russian tanks rolled into Hungary in 1956.

Dissenting voices had long argued that Putin’s risk appetite was different. They didn’t need hindsight to know that his annexation of Crimea was a clear sign of a gambler with a penchant for recklessness. And they didn’t need it when he invaded Chechnya and Georgia, used polonium in a London hotel, downed a passenger airline, and used chemical weapons in Syria and on the streets of Salisbury in the West of England.

Despite all this, ideologically right-wing and left-wing extremists gave him comfort. And the mainstream forgot the traditional doctrine of deterrence and made a naïve foreign policy mistake.

A new geopolitical landscape At the time of this writing, the military implications are unclear and publishing deadlines would likely render hollow any forecasts. Whatever military scenario plays out, this war will fundamentally change the world’s geopolitical landscape.

Cold War II looms. A new wall may not be built, but seeing a Europe that is not sharply divided between West and East again is difficult. In Russia, future living standards look as grey as they did during Cold War I, with a depression following a 30% contraction in GDP and hyperinflation.

The impacts in Western Europe will be different. For one, NATO, perhaps with Finland and Sweden as new members, will be strengthened, as the threat from Putin is finally clear to all. Helping the cause will be a US recommitted to international defense and the Atlantic Alliance.

In addition, the EU has been remarkably emboldened since the invasion, quickly discovering the need for rearmament and the benefits of strategic autonomy and self-sufficiency. It will now surely grasp the opportunity to become a defense union and superpower in its own right, taking its place alongside the US and China in international affairs. That opportunity has been made possible by Germany’s policy volt-face after a decade of Russian appeasement to full and active military involvement. Chancellor Olaf Scholz has promised to increase German defense spending to 2% of GDP and to invest a one-off sum of €100 billion, twice the country’s annual defense budget.

Critical to the EU’s rise is Emmanuel Macron, now the de facto leader of Europe. He will now be re-elected easily as president of France. (His main opponent, Marine Le Pen, had to pulp her election brochures, as they included a picture of her shaking hands with Putin.)

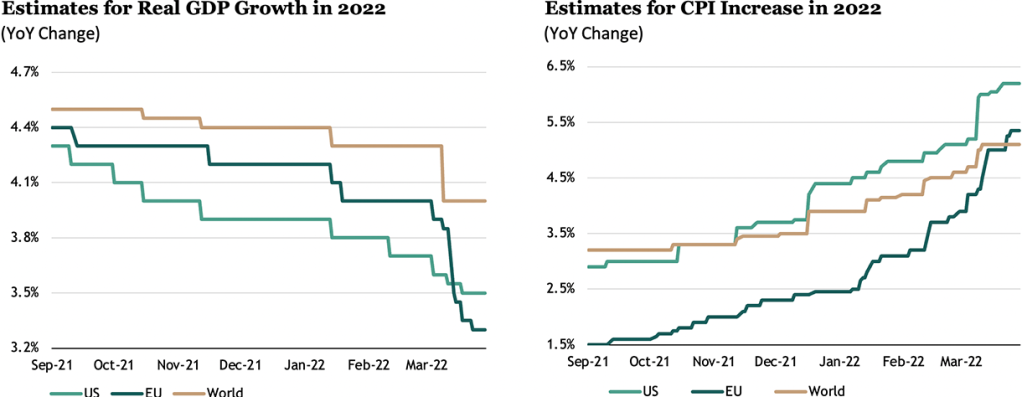

Energy crisis to strain wallets, democracies Energy prices, soaring as a result of an oil and gas supply crisis complicated by perhaps ten million displaced Ukrainians entering Western Europe, will put severe strains on less temperate democracies than France and Germany. Expect that extremists attempt to exploit shakier democracies, but fail. Their tacit support for Putin has undermined them, and the politics of war has strengthened the case for internationalism and underlined the dangers of nationalism.

The cost-of-living increases will hurt, particularly in the UK. Russian gas represents just 5% of UK supply, compared to 50% in Germany and Italy and almost 100% in Finland and Latvia. But while the Brits may get most of their gas from the North Sea and Norway, they’re sold on the open market. With UK gas storage capacity now minimal, the UK depends on fluctuations in prices, which will remain high as Europe turns away from Russian supply. There could be a real political impact from the combination of diminishing disposable income and Chancellor Rishi Sunak’s limited ability to offer tax cuts and other economic sweeteners.

Russia, an uncertain future Many expect the invasion of Ukraine to bring about fundamental change in Russia, but it took 12 years for the USSR to collapse after its invasion of Afghanistan. The fear is that the rest of the decade will be spent arguing about war reparations and whether to seize Russian Central Bank assets to pay for them. We can certainly expect a war crimes investigation that lasts for many years. And if Putin remains in power for that process, it will poison Russian relations with the West for that much longer.