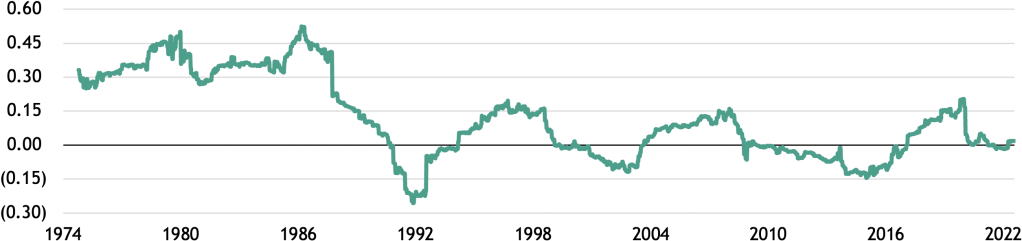

Continued Trouble for the Traditional 60/40 Portfolio

Markets remain too complacent. The efficient market hypothesis argues that all information is priced in. So with the S&P 500 and Nasdaq down more than 20% and 30%, respectively, from their trailing 52-week peaks, and the average company in each index down significantly more, an argument could be made that the market priced in the recession already. 6 But there is an apt quote, often misattributed to Mark Twain, that says, “It ain’t what you don’t know that gets you into trouble. It’s what you know for sure that just ain’t so.”

Record profit margins: Just ain’t so Stickier inflation, elevated wage growth and a higher cost of capital are all ingredients that place downward pressure on profit margins. In addition, a strong US dollar and a trend away from globalization are additional pressures for large multinational companies (like many of the constituents of the S&P 500) that have high shares of revenues from abroad and/or have highly globalized supply chains. Despite all of these headwinds, analysts continue to forecast record profit margins for the S&P 500 next year. Consensus expectations for margins have moderated somewhat in recent months, but their forecasts still point to profit margins that would be higher than at any point pre-COVID. Those forecasts are likely to be revised down even further in the coming months, along with those for earnings.

Earnings forecasts need to be revisited This bear market has the S&P 500 down to a 16x forward P/E multiple, but the drop is almost entirely due to price declines, as until quite recently, earnings forecasts remained elevated. But in every recession in the last 50 years, earnings growth declined by an average of around 10% from peak to trough. I am skeptical that earnings growth will remain positive, so I’m wary of the rosy profits forecast, and the 16x multiple. For comparison, markets historically trough at roughly a 13x multiple in recessions, on average.

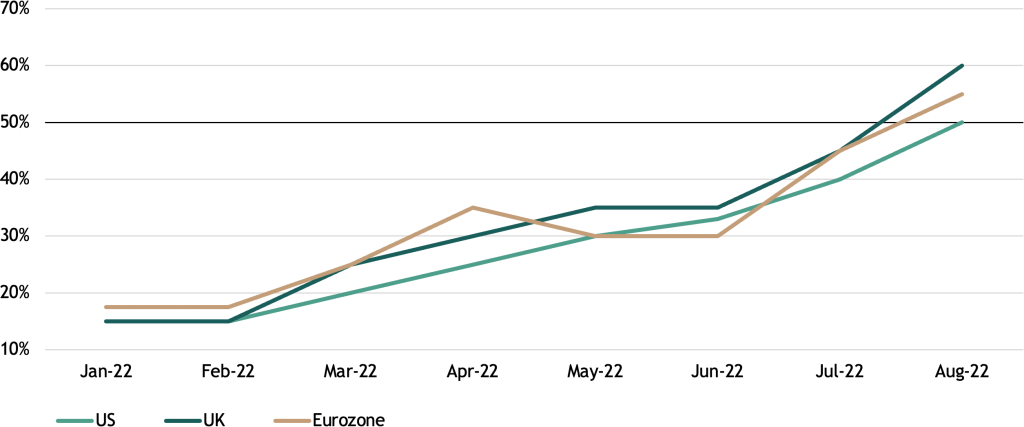

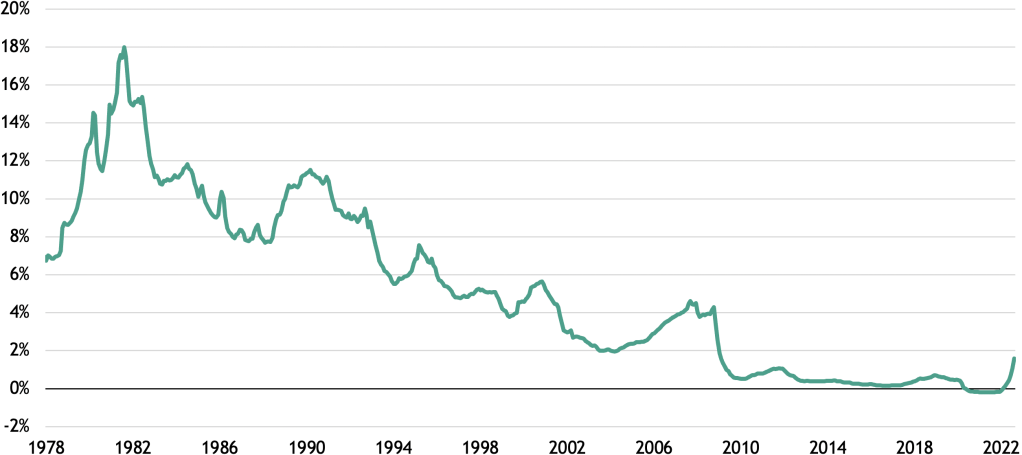

A durable turnaround in global rates A forty-year trend of secularly falling interest rates has stalled, if not ended completely. Over that period, the average of global rates hit an all-time low. Today, short-term sovereign bond yields for G7 countries hover around an average of 2% (see Figure 2). We are in the midst of one of the most coordinated tightening cycles in recent memory, with approximately 85% of central banks currently hiking policy rates. Even so, rates are still low from an historical perspective, as the chart shows. The recent rise in interest rates, while rapid, has further to go. One reason for that is a secular trend of underinvestment.

Figure 2: Average of G7 Countries’ Short-Term Interest Rates 7

Already-constrained supply meets boosted demand If one is to believe that inflation will be conquered and permanently return to ultra-low levels, then it would also be reasonable to assume that interest rates will return to record lows. However, as we discussed in our August essay, there are decades of underinvestment to contend with. Globalization enabled the US to rely on decades of cheap imports, while capital spending as a share of GDP declined in manufacturing. This was not problematic when excess slack in the economy never got used up, and US output never bumped up against potential growth. This underinvestment in supply was laid bare when the fiscal policy response to COVID suddenly boosted demand. In the US, that stimulus translated into a benefit of approximately $28,000 per capita. For comparison, the New Deal era produced a total benefit of $6,280 per capita in today’s dollars. 8

Higher rates for longer challenge traditional fixed income The Fed and other central banks will slow demand cyclically. However, as mentioned in the August essay, investment spending is sensitive to rising rates. That means that the current fight against inflation may well lead to further underinvestment in the short term. That could exacerbate shortages and subsequently lead to a resurgence in inflationary pressures after the economy starts to recover. The shortages going in could be the shortages coming out, particularly in areas like housing and energy supply. Because of this, central banks may not be keen to immediately cut rates to zero (or at least not for very long) to ward off slowing growth. I am of the view that traditional fixed income will continue to be challenged by higher interest rates as a result.

Bonds, even those with higher interest rates, will just be clipping coupons, the real value of which will be lower because of stickier inflation. For their part, equity investors will be structurally challenged to achieve the returns of the previous cycles due to higher interest rates and the reversal, at least in part, of the unprecedented balance sheet expansions of the major central banks.

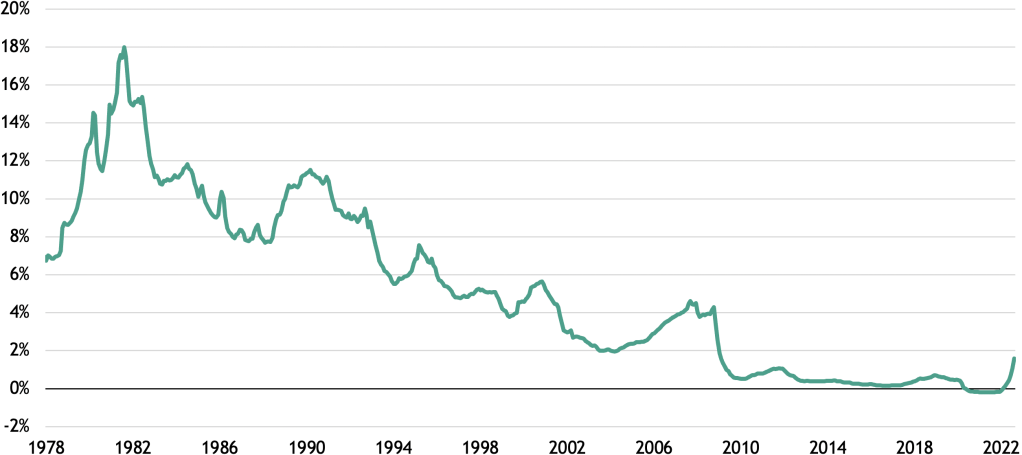

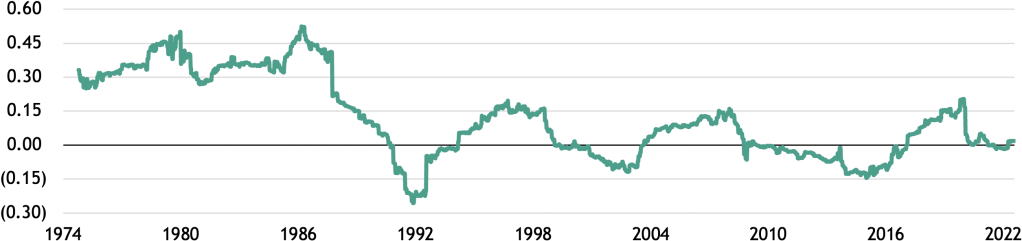

Rethinking stock / bond correlations I do not believe that the recent trouble for 60/40 portfolios is a one-time aberration. When considering diversification, it’s important to remember that correlations are not static. They change over time, and they can remain positively or negatively correlated for long periods, especially in rising rate environments, as illustrated in Figure 3. As the chart illustrates, in the late 1970s and much of the 1980s, when rates were high and generally rising, the correlation was strongly positive for a sustained period.

Figure 3: Stock / Bond Correlation 9

(rolling 5-year)

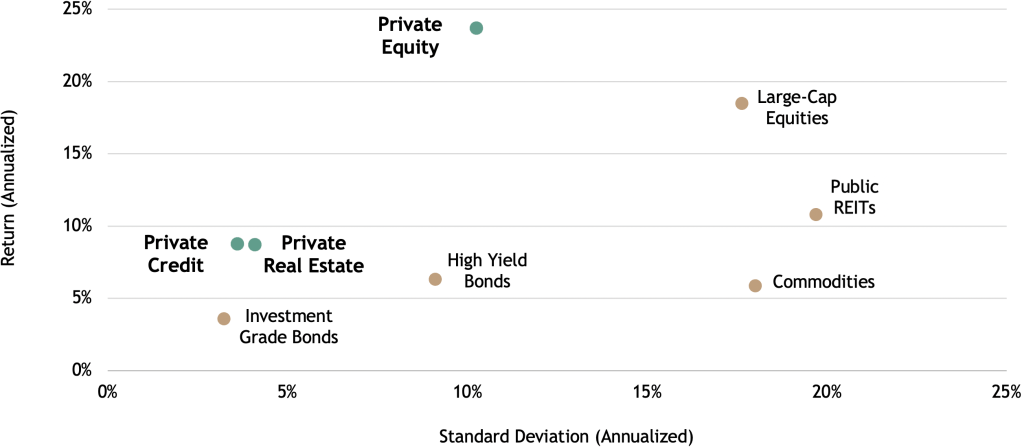

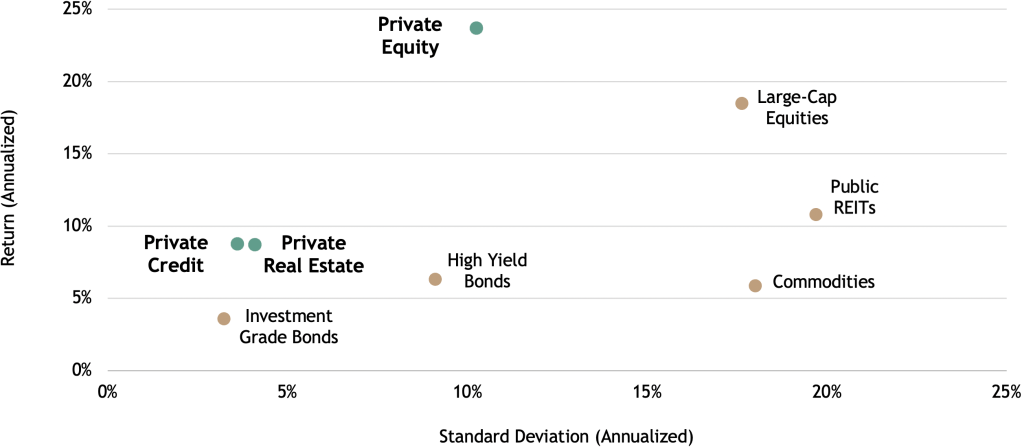

Reconfiguring the diversification toolkit In my opinion, the US will not return to a low rate / low inflation environment in the short term, so today’s positive correlation could persist for some time. Within that framework, investors need to consider new tools for their toolkits so they can still maintain an edge in the pursuit of attractive risk-adjusted returns. Alternative assets are one such potential solution, as returns tend to be less correlated to traditional public market returns, and often have lower volatility. Figure 4 shows how certain alternative asset classes have exhibited strong historical risk-adjusted returns compared to several commonly owned public assets. We plan to write more in the coming weeks about alternative assets and the potential diversification benefits they can offer for certain portfolios.

Figure 4: Historical Risk and Return of Select Asset Classes (2017–2021) 10

Themes and sectors for the long term—and our November essay Despite all the challenges, I expect a number of secular themes and sectors, particularly those tied to energy security and the global energy transition, to present exciting opportunities for investors. We will discuss these topics in much greater detail in next month’s essay, which I will co-author with Dr. Jean Rogers, Blackstone’s Global Head of ESG.

With data and analysis by Taylor Becker.