Insights

Market Views: Is Everything a Bubble?

Blackstone President Jon Gray debunks the “bubbles” in today’s economy and shares his take on navigating the moment as an investor.

Market Views

Why Should You Care About Data Centers?

Market Views

Real Estate Enters the Next Phase of the Cycle

Portfolio Insights

Vision, Ambition, and Humanity in the Age of AI: Insights from Blackstone’s CEO Conference

Investment Strategy

Private Credit Beyond the Noise

Portfolio Insights

Behind the Scenes: Inside QTS with Farhad Karim

Market Views

The Deal Dam is Breaking

Investment Strategy

Rethinking the 60%

Firm News

40 Years in 40 Seconds

Firm News

Steve Schwarzman & Jon Gray in Conversation

Portfolio Insights

Powering the Future: Blackstone’s Investments across the Energy Value Chain

Portfolio Insights

Supporting Opportunity Through Shared Ownership

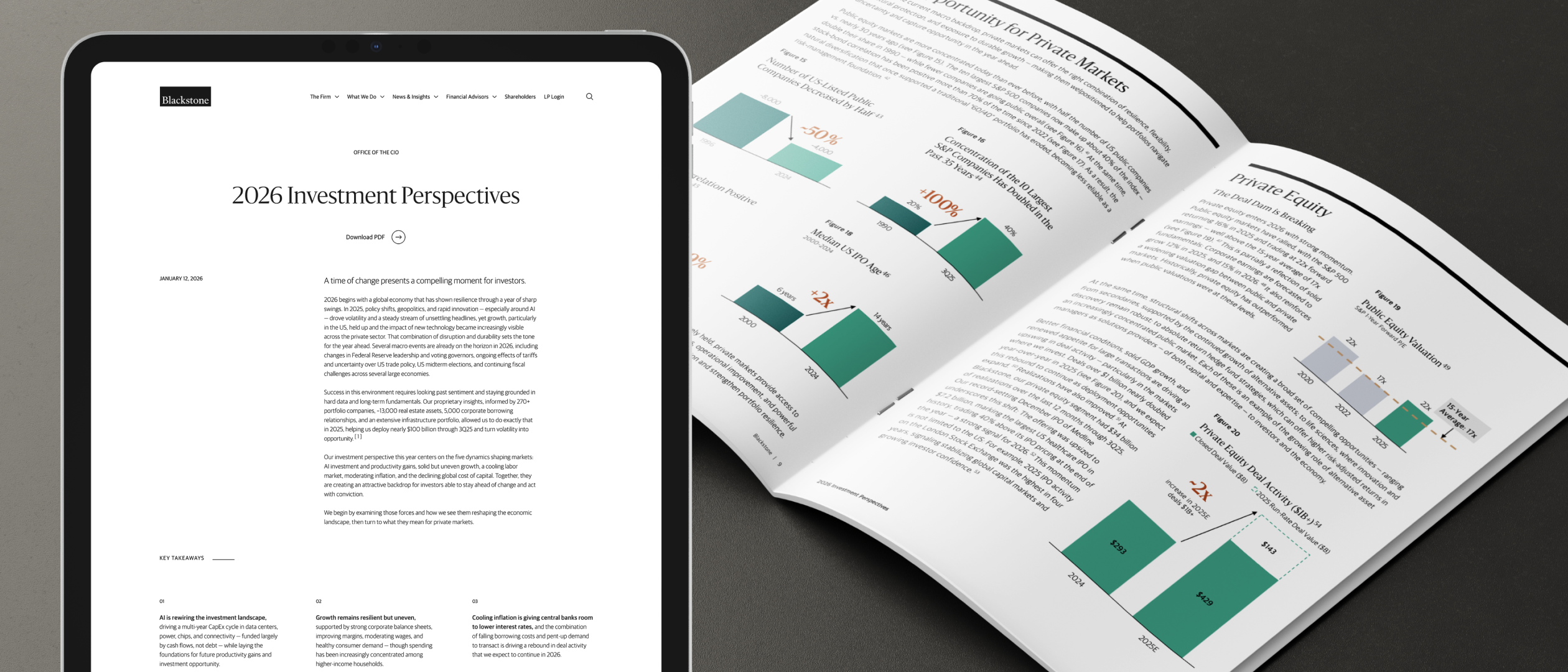

Market Views